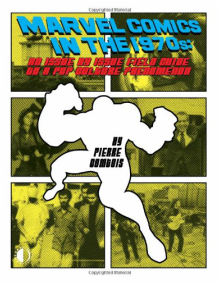

By popular demand (because Joe Popular demanded it!) Twomorrows Publishers will present Marvel Comics in the 1970s: An Issue by Issue Field Guide to a Pop Culture Phenomenon covering the long twilight years of Marvel’s history. In volume one, Marvel Comics in the 1960s, readers saw how the development of Marvel Comics’ new line of super-hero books could be broken up into four distinct phases: the formative years, the years of consolidation, the grandiose years, and the twilight years. All fourwere led by editor/writer Stan Lee allied with some of the best artists in the business including Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, John Romita, John Buscema, Jim Steranko, and Gene Colan. But where volume one ended with the grandiose years, Marvel Comics in the 1970sMarvel Comics in the 1970s covers the company’s final phase: the twilight years. A full decade of pop-culture history that saw Lee’s role as writer diminish, the stunning departure of Jack Kirby, the rise of Roy Thomas as editor, and the introduction of a new wave of writers and artists who would expand the boundaries of comics beyond super-heroes while planting the seeds for the industry’s eventual self-destruction. So don’t be satisfied with only half a loaf! Demand your full share! Check out and find out why Marvel was once known as The House of Ideas!

Watch Pierre Comtois's interview about Marvel Comics in the 1970s with Groton Channel News here!

From the introduction:

In volume one, Marvel Comics in the 1960s, it was shown how the development of the company’s new line of super-hero books introduced in that decade could be broken up into four distinct phases: the formative years, the years of consolidation, the grandiose years, and the twilight years. Led by editor Stan Lee, allied with some of the best artists in the business including Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, John Romita, John Buscema, Jim Steranko, and Gene Colan, Marvel moved quickly from its early years when concepts involving continuity and characterization were introduced to new features with little thought given to their revolutionary impact on the industry to the years of consolidation when concepts of characterization, continuity, and realism began to be actively applied. In the grandiose years, Marvel’s growing popularity among older readers and the counter culture as well as some limited attempts at merchandising spurred Lee and top writer Roy Thomas to incorporate contemporary concerns about race, the environment, the anti-war movement, and feminism into sprawling stories of outsized characters and concepts that frequently took the universe itself as their setting rather than restrictive confines of Earth. Taken together, it was a heady mix vaulting Marvel Comics into a pop-culture movement that threatened to overwhelm established notions of art and its role in society. As a result, Lee came to be seen as Marvel’s front man and through a combination of speech making, magazine interviews, and his often inspiring comic book scripts, became a sort of pop guru to many of his youthful readers. However, by 1968, Marvel Comics had reached the zenith in terms of its development and sheer creative power. Soon after came an expansion of the company’s line of titles and a commensurate dilution of the talent that had made its first years great. By then, it had lost the services of Ditko and soon Kirby would leave as well, artists who’d been instrumental in the creation of some of the company’s most enduring characters. After 1970, Lee himself would begin a slow retreat from active scripting and day to day management of his comics. It was the beginning of the fourth phase of Marvel’s development: the twilight years.

Characterized by a combination of a growing lethargy among the company’s established titles and the rise of imaginative new features produced by young creators who’d been fans before they became professionals, the twilight era was the longest and most drawn out of the four phases. Those looking for a clear line of demarcation between the grandiose years and the twilight years however, will be disappointed. Like the previous phases, the change from one era to the next wasn’t obvious, coming gradually, almost imperceptibly and unlike those earlier phases, the period of overlap between the grandiose years and the twilight years is a lengthy one. And despite the temptation to use Jack Kirby’s departure from the company as marking the end of the grandiose years, the fact is, no era can be demarcated by a single event. In fact, it’s the contention here that Marvel’s exit from the silver age began almost two full years before Kirby left.

Begun in the triumphant glow of the grandiose years, this final era in silver age Marvel’s development wound down slowly as the once vibrant dynamism of Lee, Kirby, Ditko, and Heck became spent, the visual skills of their successors Romita, Buscema, and Colan for a time held their ground, and new writers like Roy Thomas, Gerry Conway, and Doug Moench steered their most creative energies away from the books that had become the bedrock of the line. As the changeover from the old guard to the new was completed and the company entered fully into its final phase (a phase whose elements and style of storytelling became as different in their sensibilities from those of the three earlier phases as those phases had been different from comics produced before Marvel’s revolution), the twilight years became a kind of epilogue to what had gone before as the long night of mediocrity slowly settled over the company.

For his part, Stan Lee had always yearned for success outside the narrow confines of the comics industry and with the success of Marvel Comics, he found an opening that allowed him scope for his ambitions. It began simply with college lecture tours during the years of consolidation and grandiose years culminating in the Carnegie Hall gig in 1972; then, as Marvel’s super heroes began to achieve iconic status, Hollywood beckoned and Lee became the company’s spokesman and chief salesman with tinseltown’s wheelers and dealers. When Marvel Comics passed out of the control of Martin Goodman and was acquired by a succession of corporations and Wall Street investors, Lee found himself promoted to publisher and eventually relinquished almost all of his writing and editorial chores to Roy Thomas who’d been prepared to take over the job for some years. Except for the occasional special issue or his scripting on the long running Spider-Man newspaper strip, Lee left the Marvel offices permanently in the 1980s and moved to California to become the company’s deal maker in Hollywood.

Before Lee’s departure however, Marvel had lost artist Jack Kirby whose dissatisfaction with Lee’s stardom and loss of control over characters he had helped to create, prompted him to look for greener pastures. Kirby’s frustration had begun to be apparent long before he actually announced his decision to depart when his art on the Fantastic Four and Thor strips began to flag. There was less energy there and the inventiveness that had defined the strips in the years of consolidation and grandiose years was noticeably absent even after he had been given more, if not complete, control over the plotting. Preceding Lee to the West Coast, Kirby had locked himself out of any chance for a permanent position within the company and when he began to consider the radical thought of leaving Marvel, the only real option by the early seventies was rival DC with whom he signed an exclusive contract in 1970 that allowed him unprecedented freedom from editorial control. But even Kirby’s personal store of energy wasn’t limitless and having already passed his creative peak while at Marvel, he failed to duplicate at DC the amazing successes of the previous ten years when his ambitious “Fourth World” concept involving a series of interconnected books fell short of expectations and were soon canceled. Disappointed with his experience at DC, Kirby returned to Marvel in 1975 where he was given the same kind of editorial freedom. But for those readers who looked forward to seeing him back, Kirby proved a disappointment. If he wasn’t working on new titles of his own invention, he was ignoring one of the most important aspects of Marvel’s success with readers, the continuity among its titles. In taking over the books of two characters with whom he had been previously identified, Captain America and the Black Panther, Kirby defeated readers’ expectations by ignoring previous storylines as if they’d never happened. Such an attitude toward the Marvel universe and its characters didn’t endear him either to the readers or his editors and as the years passed, Kirby became all but irrelevant. When his association with Marvel finally ended in 1979, he dabbled with smaller independent companies before leaving comics more or less for good in favor of the more lucrative animation industry.

In the meantime, Don Heck, finding work drying up at Marvel, had also migrated to DC. Heck followed in the footsteps of Steve Ditko who’d been the first of Marvel’s trio of founding artists to leave the company in 1966. Ditko lingered at DC for only a short time before moving on to former employer Charleton Comics and from there began working with a series of independent publishers to produce some of the most eclectic, idiosyncratic material of his career. Those artists such as John Romita, John Buscema, and Gene Colan, who had followed Kirby, Ditko, and Heck to Marvel during the years of consolidation had since progressed beyond their early tutelage under Kirby to become hugely popular for their own distinctive styles. They became the bedrock upon which a new foundation would be raised made up of fans turned professional who joined the company in the 1970s. Younger artists such as Barry Smith and Jim Steranko would progress quickly and prove influential beyond the limited number of pages they produced and move on to other fields. Finally, as the 1970s passed mid-decade, the era of the old time professional writer and artist passed away and the comics industry was given over to the fan creator who had grown up reading, collecting, and enjoying comics and who was fired by a determination to turn what had been a passion into a career.

After Lee became publisher, Thomas was at last promoted to editor-in-chief at Marvel and began his tenure presiding over a new renaissance of creativity. Begun under Lee’s guidance, it was made possible after the Comics Code Authority loosened some of its regulations allowing for, among other things, the reintroduction of the horror comic. Taking advantage of the opening, Marvel launched new features based on the old Universal Studios monsters and a plethora of try-out titles that hosted different, original characters every month many of which graduated into their own titles. With the introduction of the horror books, the company’s line of comics suddenly became far too much for any single person to supervise. Swamped in work, Thomas was unable to keep up and writers soon found themselves with a new freedom that resulted in a slew of eclectic features that included Man-Thing, Howard the Duck, Jungle Action, War of the Worlds and a host of black and white magazine titles. But with all the new, exciting features, came a concurrent loss of control over production. Deadlines were missed with increasing regularity, reprints had to be substituted for work not submitted in time, some titles became half original material and half reprint, shipping dates were missed, some work was even printed directly from the artist’s pencils without benefit of an inker’s polish. In response, writers were allowed to become their own editors further fragmenting editorial control. Under the increasing pressure and frustrated at not having the time to pursue his own writing projects, Thomas resigned as editor-in-chief to be replaced by a number of successors including Gerry Conway but none of them remained on the job for long. The slide into editorial chaos was only stopped in the 1980s with the arrival of Jim Shooter who had begun his career in comics as a teenager writing scripts for DC. Shooter imposed much needed discipline at Marvel and restored order to the company but his methods alienated a number of employees, including Thomas himself, who eventually quit and moved to DC.

Through all these changes the twilight years moved on beyond the 1970s and into the 1980s as a kind of atrophy began to set in on the company’s older, established titles that had once led the Marvel revolution. Although humor became stale, formula trumped originality, and elements such as characterization and realism began to fade from such former trendsetters as Spider-Man and Fantastic Four, the irony was that they continued to outsell the oddball books and new features that often showed the creativity that had originally set Marvel apart from its competitors. And so, as the twilight era faded out, and memory of the glorious triumphs of the earlier phases dimmed, an air of somnambulism crept into Marvel, only to be jarred into wakefulness when, at intervals, rising creative stars occasionally shook it from its slumber. The years would stretch into decades and reach beyond the scope of this work as flashes of creativity, the last echoes of Marvel’s fabled silver age (such as that of John Byrne’s stint on the X-Men and Fantastic Four, Frank Miller’s work on Daredevil and the Roger Stern, John Buscema, Tom Palmer team up on the Avengers), became more and more infrequent until flickering out completely.

Watch Pierre Comtois's interview about Marvel Comics in the 1970s with Groton Channel News here!

From the introduction:

In volume one, Marvel Comics in the 1960s, it was shown how the development of the company’s new line of super-hero books introduced in that decade could be broken up into four distinct phases: the formative years, the years of consolidation, the grandiose years, and the twilight years. Led by editor Stan Lee, allied with some of the best artists in the business including Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, John Romita, John Buscema, Jim Steranko, and Gene Colan, Marvel moved quickly from its early years when concepts involving continuity and characterization were introduced to new features with little thought given to their revolutionary impact on the industry to the years of consolidation when concepts of characterization, continuity, and realism began to be actively applied. In the grandiose years, Marvel’s growing popularity among older readers and the counter culture as well as some limited attempts at merchandising spurred Lee and top writer Roy Thomas to incorporate contemporary concerns about race, the environment, the anti-war movement, and feminism into sprawling stories of outsized characters and concepts that frequently took the universe itself as their setting rather than restrictive confines of Earth. Taken together, it was a heady mix vaulting Marvel Comics into a pop-culture movement that threatened to overwhelm established notions of art and its role in society. As a result, Lee came to be seen as Marvel’s front man and through a combination of speech making, magazine interviews, and his often inspiring comic book scripts, became a sort of pop guru to many of his youthful readers. However, by 1968, Marvel Comics had reached the zenith in terms of its development and sheer creative power. Soon after came an expansion of the company’s line of titles and a commensurate dilution of the talent that had made its first years great. By then, it had lost the services of Ditko and soon Kirby would leave as well, artists who’d been instrumental in the creation of some of the company’s most enduring characters. After 1970, Lee himself would begin a slow retreat from active scripting and day to day management of his comics. It was the beginning of the fourth phase of Marvel’s development: the twilight years.

Characterized by a combination of a growing lethargy among the company’s established titles and the rise of imaginative new features produced by young creators who’d been fans before they became professionals, the twilight era was the longest and most drawn out of the four phases. Those looking for a clear line of demarcation between the grandiose years and the twilight years however, will be disappointed. Like the previous phases, the change from one era to the next wasn’t obvious, coming gradually, almost imperceptibly and unlike those earlier phases, the period of overlap between the grandiose years and the twilight years is a lengthy one. And despite the temptation to use Jack Kirby’s departure from the company as marking the end of the grandiose years, the fact is, no era can be demarcated by a single event. In fact, it’s the contention here that Marvel’s exit from the silver age began almost two full years before Kirby left.

Begun in the triumphant glow of the grandiose years, this final era in silver age Marvel’s development wound down slowly as the once vibrant dynamism of Lee, Kirby, Ditko, and Heck became spent, the visual skills of their successors Romita, Buscema, and Colan for a time held their ground, and new writers like Roy Thomas, Gerry Conway, and Doug Moench steered their most creative energies away from the books that had become the bedrock of the line. As the changeover from the old guard to the new was completed and the company entered fully into its final phase (a phase whose elements and style of storytelling became as different in their sensibilities from those of the three earlier phases as those phases had been different from comics produced before Marvel’s revolution), the twilight years became a kind of epilogue to what had gone before as the long night of mediocrity slowly settled over the company.

For his part, Stan Lee had always yearned for success outside the narrow confines of the comics industry and with the success of Marvel Comics, he found an opening that allowed him scope for his ambitions. It began simply with college lecture tours during the years of consolidation and grandiose years culminating in the Carnegie Hall gig in 1972; then, as Marvel’s super heroes began to achieve iconic status, Hollywood beckoned and Lee became the company’s spokesman and chief salesman with tinseltown’s wheelers and dealers. When Marvel Comics passed out of the control of Martin Goodman and was acquired by a succession of corporations and Wall Street investors, Lee found himself promoted to publisher and eventually relinquished almost all of his writing and editorial chores to Roy Thomas who’d been prepared to take over the job for some years. Except for the occasional special issue or his scripting on the long running Spider-Man newspaper strip, Lee left the Marvel offices permanently in the 1980s and moved to California to become the company’s deal maker in Hollywood.

Before Lee’s departure however, Marvel had lost artist Jack Kirby whose dissatisfaction with Lee’s stardom and loss of control over characters he had helped to create, prompted him to look for greener pastures. Kirby’s frustration had begun to be apparent long before he actually announced his decision to depart when his art on the Fantastic Four and Thor strips began to flag. There was less energy there and the inventiveness that had defined the strips in the years of consolidation and grandiose years was noticeably absent even after he had been given more, if not complete, control over the plotting. Preceding Lee to the West Coast, Kirby had locked himself out of any chance for a permanent position within the company and when he began to consider the radical thought of leaving Marvel, the only real option by the early seventies was rival DC with whom he signed an exclusive contract in 1970 that allowed him unprecedented freedom from editorial control. But even Kirby’s personal store of energy wasn’t limitless and having already passed his creative peak while at Marvel, he failed to duplicate at DC the amazing successes of the previous ten years when his ambitious “Fourth World” concept involving a series of interconnected books fell short of expectations and were soon canceled. Disappointed with his experience at DC, Kirby returned to Marvel in 1975 where he was given the same kind of editorial freedom. But for those readers who looked forward to seeing him back, Kirby proved a disappointment. If he wasn’t working on new titles of his own invention, he was ignoring one of the most important aspects of Marvel’s success with readers, the continuity among its titles. In taking over the books of two characters with whom he had been previously identified, Captain America and the Black Panther, Kirby defeated readers’ expectations by ignoring previous storylines as if they’d never happened. Such an attitude toward the Marvel universe and its characters didn’t endear him either to the readers or his editors and as the years passed, Kirby became all but irrelevant. When his association with Marvel finally ended in 1979, he dabbled with smaller independent companies before leaving comics more or less for good in favor of the more lucrative animation industry.

In the meantime, Don Heck, finding work drying up at Marvel, had also migrated to DC. Heck followed in the footsteps of Steve Ditko who’d been the first of Marvel’s trio of founding artists to leave the company in 1966. Ditko lingered at DC for only a short time before moving on to former employer Charleton Comics and from there began working with a series of independent publishers to produce some of the most eclectic, idiosyncratic material of his career. Those artists such as John Romita, John Buscema, and Gene Colan, who had followed Kirby, Ditko, and Heck to Marvel during the years of consolidation had since progressed beyond their early tutelage under Kirby to become hugely popular for their own distinctive styles. They became the bedrock upon which a new foundation would be raised made up of fans turned professional who joined the company in the 1970s. Younger artists such as Barry Smith and Jim Steranko would progress quickly and prove influential beyond the limited number of pages they produced and move on to other fields. Finally, as the 1970s passed mid-decade, the era of the old time professional writer and artist passed away and the comics industry was given over to the fan creator who had grown up reading, collecting, and enjoying comics and who was fired by a determination to turn what had been a passion into a career.

After Lee became publisher, Thomas was at last promoted to editor-in-chief at Marvel and began his tenure presiding over a new renaissance of creativity. Begun under Lee’s guidance, it was made possible after the Comics Code Authority loosened some of its regulations allowing for, among other things, the reintroduction of the horror comic. Taking advantage of the opening, Marvel launched new features based on the old Universal Studios monsters and a plethora of try-out titles that hosted different, original characters every month many of which graduated into their own titles. With the introduction of the horror books, the company’s line of comics suddenly became far too much for any single person to supervise. Swamped in work, Thomas was unable to keep up and writers soon found themselves with a new freedom that resulted in a slew of eclectic features that included Man-Thing, Howard the Duck, Jungle Action, War of the Worlds and a host of black and white magazine titles. But with all the new, exciting features, came a concurrent loss of control over production. Deadlines were missed with increasing regularity, reprints had to be substituted for work not submitted in time, some titles became half original material and half reprint, shipping dates were missed, some work was even printed directly from the artist’s pencils without benefit of an inker’s polish. In response, writers were allowed to become their own editors further fragmenting editorial control. Under the increasing pressure and frustrated at not having the time to pursue his own writing projects, Thomas resigned as editor-in-chief to be replaced by a number of successors including Gerry Conway but none of them remained on the job for long. The slide into editorial chaos was only stopped in the 1980s with the arrival of Jim Shooter who had begun his career in comics as a teenager writing scripts for DC. Shooter imposed much needed discipline at Marvel and restored order to the company but his methods alienated a number of employees, including Thomas himself, who eventually quit and moved to DC.

Through all these changes the twilight years moved on beyond the 1970s and into the 1980s as a kind of atrophy began to set in on the company’s older, established titles that had once led the Marvel revolution. Although humor became stale, formula trumped originality, and elements such as characterization and realism began to fade from such former trendsetters as Spider-Man and Fantastic Four, the irony was that they continued to outsell the oddball books and new features that often showed the creativity that had originally set Marvel apart from its competitors. And so, as the twilight era faded out, and memory of the glorious triumphs of the earlier phases dimmed, an air of somnambulism crept into Marvel, only to be jarred into wakefulness when, at intervals, rising creative stars occasionally shook it from its slumber. The years would stretch into decades and reach beyond the scope of this work as flashes of creativity, the last echoes of Marvel’s fabled silver age (such as that of John Byrne’s stint on the X-Men and Fantastic Four, Frank Miller’s work on Daredevil and the Roger Stern, John Buscema, Tom Palmer team up on the Avengers), became more and more infrequent until flickering out completely.

To buy this book: